For nearly 90 years, Flin Flon has been known for bone-chilling winters, hard-rock mining and rough-and-tumble hockey.

And for almost 10 of those years, marijuana – medicinal marijuana, to be precise – was added to the list of familiar characteristics.

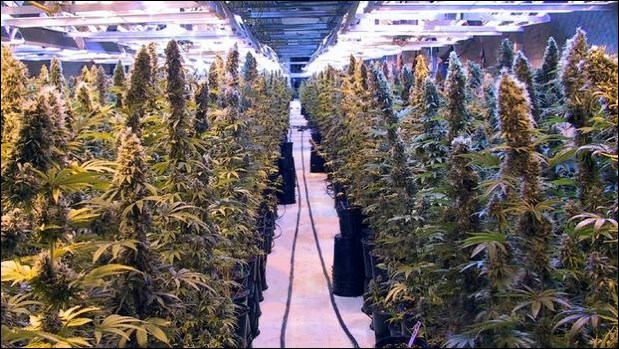

Beneath our feet, in vacant space at the now-defunct Trout Lake mine near Flin Flon, a state-of-the-art growth chamber produced medical pot for seriously ill Canadians from 2001 to 2009.

Yet some always believed marijuana was just the start, that the secure confines of the mine would one day yield plant-based medical advances capable of rewriting medical textbooks.

In time, ambitious predictions of 200 jobs for the facility would abound. It seemed plausible that Flin Flon had found its secondary industry in the same place as its primary one – within rocky, subterranean tunnels blasted out of the Canadian Shield.

Then one day, with little explanation, it all came to an end.

The announcement

Flin Flonners were settling into the holidays on Dec. 23, 2000, when the federal government interrupted the family get-togethers and present-wrapping with some surprising news.

Health Canada had awarded a contract to a private biotech firm to supply marijuana for medicinal purposes – and the pot was going to originate in

Flin Flon.

Saskatoon-based Prairie Plant Systems (PPS) was tasked with growing up to 400 kg of cannabis per year over the next five years (with contract extensions to follow). To accomplish this, PPS would build a $1.1-million facility underground, using unoccupied space at the Trout Lake mine operated by HBM&S (now Hudbay).

By then, PPS had already been working with HBM&S for a decade to produce a variety of plant specimens in an underground growth chamber at Flin Flon’s South Main mine.

“Originally, we grew roses, tomatoes and then quite a number of species of pharmaceutical crops,” Wayne Fraser, director of environmental control at HBM&S, told The Reminder at the time.

Then-federal health minister Allan Rock proclaimed the establishment of a sanctioned medical marijuana supplier showed “Canada is acting compassionately” to help “people who are suffering from grave and debilitating illness.”

Rock emphasized the pot would be made available to patients authorized to use it and who agreed to provide information to Health Canada for monitoring and research purposes.

It was expected the Trout Lake facility would create eight to 10 new permanent jobs – and perhaps many more in the future.

Marijuana capital

Many Flin Flonners saw little significance in the PPS announcement. After all, relatively few people were involved in the project, and access to the Trout Lake facility was highly restricted.

Others saw a unique business opportunity. In February 2001, The Zig Zag Zone, a now-defunct local novelty store, began selling t-shirts touting Flin Flon as the “Marijuana Growing Capital of Canada.”

The shirts depicted a miner – played by Flintabbatey Flonatin – pushing a rail car filled with marijuana leaves out of a mine. In the background, a towering joint filled in for the smoke stack, with musical notes and the lyrics “High ho, high ho, it’s off to work we grow” replacing the clouds of smoke.

Some residents were unimpressed, fearing the shirts linked Flin Flon to the illicit street version of weed rather than the medicinal variety. Zig Zag Zone owner Chris Pilz told reporters he was not condoning the use of illegal drugs and was just having fun with the community’s newfound industry.

The shirts gained some media attention, but it was nothing compared to the bonanza that came on

Aug. 2, 2001 when reporters flocked to Trout Lake mine for the official opening of the growth chamber. One source said the news even made CNN.

Allan Rock, then the health minister, was the guest of honour at the ceremony.

“Now that I have come from Ottawa to Flin Flon to visit the site, I am even more convinced that we made the right choice,” Rock told 100 or so guests.

Within weeks of the ceremony, technicians were to begin harvesting pot buds for testing. Clinical trials would follow, then more widespread availability of marijuana to eligible patients.

Was this the start of a secondary industry? Flin Flon resident Gordon Wells didn’t think so, telling the Canadian Press at the time, “It’s just a big fuss over nothing. Everybody just laughs about it.”

But the head of PPS wasn’t laughing. Far from it.

Motivated

Brent Zettl is a highly motivated individual – which is kind of ironic considering how closely his name is associated with marijuana.

According to a Lift News profile, Zettl never smoked marijuana in high school, where he did well enough to get into university and earn a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture degree with distinction.

After co-founding PPS in 1988, Zettl, according to the profile, formulated a question: Can plant growth improve if all external influences, such as light and nutrients, are completely controlled?

That led to PPS’s work in the South Main mine shaft, which in turn led to the marijuana mine at

Trout Lake.

While there has always been debate around whether marijuana leads to other drugs, Zettl always seemed certain it would – at least for PPS.

In March 2007, he told a Flin Flon area audience that marijuana represented only the beginning of plant-derived medicine possibilities.

“Now we’re moving into an area where we have plants that actually can be turned on to produce certain proteins,” Zettl said, noting those proteins can then be used to treat diseases such as cancer and immune system deficiencies.

While the Trout Lake facility still employed relatively few people, Zettl believed it could eventually require up to 200 people. In response, at least one resident suggested local high schools offer courses to prepare students for careers at the biotech firm.

In his speech, Zettl said PPS had secured a four-year contract to develop a hepatitis C vaccine from plants. He estimated he would need another growth chamber within a year, but he could not guarantee it would be at Trout Lake.

“We have a good infrastructure here [in Flin Flon],” he said. “We intend to continue to pursue to maintain our level of interest here and try to increase it. One of the hurdles is... going to be long-term access. We do not have long-term access.”

And, as it turned out, they never would.

Closure

Word that Flin Flon’s marijuana mine would shut down caught residents by as much surprise as

Health Canada’s 2000 announcement that it would open in the first place.

In May 2009, HBM&S confirmed that PPS’s rental agreement at Trout Lake mine would expire at the end of June 2009 and would not be renewed.

Zettl made it clear he did not want to leave Trout Lake. He soon appeared before the Flin Flon and District Chamber of Commerce to make a last-ditch effort to stay.

“I think the first order of business is getting a dialogue,” he said at the time. “Right now there’s been no dialogue.”

Later, the Globe and Mail described “a row” between PPS and Hudbay over the lease. Hudbay simply said PPS’s lease was expiring and the arrangement was coming to an end.

City council did its part to back Zettl. Shortly before the facility closure, council unanimously passed a motion to support any provincial government efforts to keep PPS in Flin Flon.

In the end, PPS left as scheduled, moving its pot production to an alternate location. The company’s departure cost Flin Flon 12 full-time jobs.

As then-mayor Tom Therien told the Globe and Mail, as residents of a mining town, “We’ve survived worse than this.”

Aftermath

In 2009, the same year PPS vacated Flin Flon, a plan to study the potential of Trout Lake mine as a centre for plant-based medicine production and research was kyboshed.

The government-funded Manitoba Agri-Health Research Network said it had planned to conduct a feasibility study that year to determine which plant-based health projects might be suitable for the mine.

But Lee Anne Murphy, coordinator of the Network, told The Reminder the provincial government declined a request to fund the study.

The announcement underscored what now seemed obvious: the marijuana mine was gone, and it wasn’t coming back.

When Trout Lake mine itself closed in mid-2012, its ore sufficiently depleted, the last remnants of the once-famous marijuana mine were sealed off once and for all.

And so ended a unique economic chapter in Flin Flon history – one with seemingly so much potential that ultimately went up in smoke.