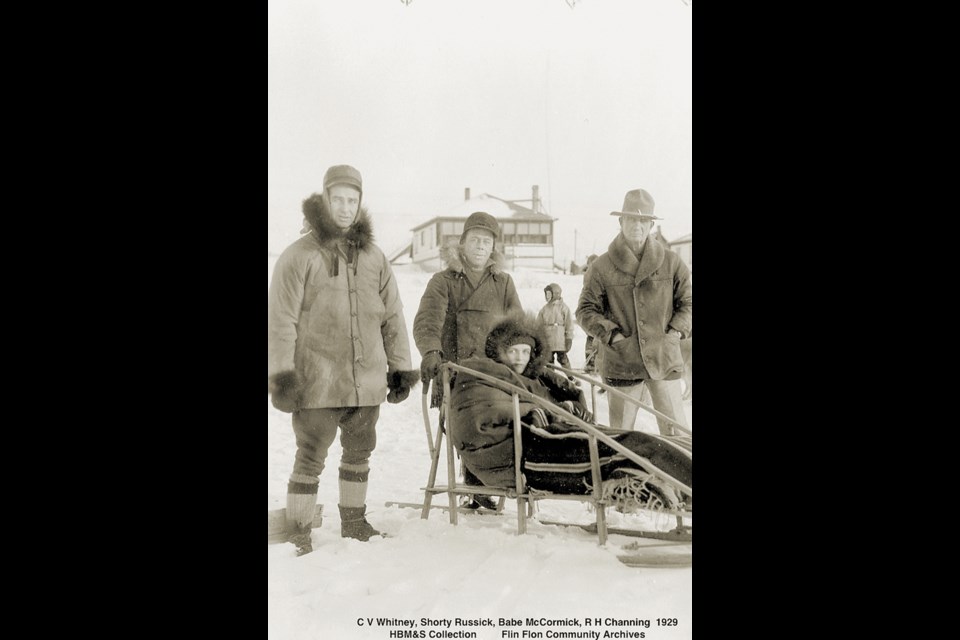

More than eight decades ago, William “Shorty” Russick did something no other Flin Flonner has done since – win an individual Olympic medal.

Russick won his hardware at the 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, NY, when sled dog racing was introduced as a demonstration sport. While some sources list his hometown as The Pas, the official record of the 1932 Olympics and multiple newspaper reports from the time period list his hometown as Flin Flon.

Information about Russick’s early life is not easy to find. A story written about Russick in the Mar. 12, 1926 issue of The Nashua Telegraph said he was born in Russia, part of a family forced to move to Siberia under the Tsarist regime. Russick and some of his family immigrated to New York City shortly before World War I.

Disliking the city, Russick moved to Canada to get lost in the wilderness, heading to The Pas for a job in the lumber industry. Unsatisfied, Russick moved further into the woods to a fledgling little mining camp with a funny name – Flin Flon.

For the rest of his life, Shorty Russick would live between Pelican Narrows, The Pas and Flin Flon, first working in the mines, then trapping, hunting and running a number of stores and trading posts.

Russick’s life changed in 1918, when he bought a litter of sled dogs – that were, according to his granddaughter Laurel Dunlop, part dog and part wolf.

“I’m get lonsom op t’ere so I’m buy a leeter. Jus’ pups and I’m pay 25 dollaire for t’em,” Russick was quoted as saying in The Nashua Telegraph.

Starting in the early 1920s, Russick’s new sled dog team – Mohegan, Snap, Ginger, Silver, Murphy, Ring and Frank – became one of Canada’s quickest groups. Russick ran the dogs in races across Canada and the United States and achieved great results.

Russick and his pups were sometimes bankrolled by Chicago businessman Harold Sutton, but often times Russick was able to pay for their considerable travel expenses himself. In the ’20s, winning a prominent sled dog race could net the champion team $2,500 – today, worth more than $35,000. He used the cash to treat his dogs better than other racers did.

“My grandfather only fed his dogs steak,” said Dunlop.

To help lessen strain on his dogs, Russick employed a run-and-glide technique in races, running alongside the sled when conditions allowed to lessen weight on the sled.

Northern Manitoba produced a number of world-class mushers around that time, including Earl Brydges and Scotty McDonald. Along with Russick, the most famous was Emile St. Godard. Based in The Pas, St. Godard was arguably the face of the sport. St. Godard and Russick met on the podium frequently, but the occupant of the top spot changed often.

One of Russick’s most notable achievements involved a win over St. Godard and an all-time record, setting the fastest-ever time in the The Pas-Flin Flon-The Pas dog race.

In 1924, Russick won the race, finishing with a time of 23 hours and 42 minutes.

“That record has never been broken,” said Dunlop.

Dunlop added that Russick finished the 200-mile race so quickly that nobody was waiting at the finish line to certify the win. Russick had to improvise.

“He was reported to have rang the fire tower bell to let everybody know he was there,” she said. “He had done that race with six dogs and his lead dog was missing.”

While Russick and his pack built up an impressive record, the event that cemented his spot in sporting history began in 1932.

For the first time ever – and the only time, to date – sled dog racing was included as a demonstration sport at the Winter Olympics. The event saw racers do two loops of a course just over 40 kilometres long, starting and ending at the Olympic Stadium and winding around Lake Placid.

Entries in the event were determined on how teams did in various races across the continent. Five Canadian teams, including Russick and St. Godard, took part, along with seven American teams. The competition was stiff. Two racers had been part of explorer Richard E. Byrd’s Antarctic Expedition. Some teams included racers who had finished the infamous Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, a 1,500 km long slog through the Alaskan barrens. Another American entry, Norwegian-born Leonhard Seppala, had actually taken part in the sled ride that inspired the creation of the Iditarod.

The sled dog race took place weeks before the Olympics themselves, with six-dog teams leaving the stadium every ten minutes.

St. Godard and Seppala pulled away from the pack early, finishing their first lap ten minutes ahead of all other entries. Russick led the rest of the group, ending his first lap in 2:26:22 and in position for a bronze medal.

In the end, St. Godard could not be caught, winning the race by almost eight minutes over Seppala. Just under five hours after the race began, Russick and his dogs crossed the line in third place.

Shorty Russick had won Olympic bronze.

Russick and St. Godard’s medals did not count toward Canada’s official medal haul from the Olympics that year, but each received physical medals. Russick’s bronze medallion remains in his family’s possession to this day, said Dunlop.

Back in the great white north, Russick continued racing. One race, staged in Banff by film production company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, led to an example of Russick’s dedication to his dogs. While at the race, Russick befriended a film producer and actress Lillian Gish, a silent film star known as the “First Lady of American Cinema.” When Gish asked to ride along with Russick on his sled, he agreed.

Dunlop said the pair won the race, leading to an unusual offer from the producer.

“They offered my grandfather a role in a movie and he said no – he had his pups to look after,” she said.

Russick’s racing career came to sudden halt in 1936. According to writer and journalist Maggie Siggins in her book Bitter Embrace, Russick and his team were heading on a frozen lake to his Pelican Narrows trading post with a load of furs. The team came across a strip of thin ice and fell in the water. Russick saved himself by crawling to shore, but he was unable to save either his dogs or the load of furs. He never raced again.

Russick spent the rest of his life running businesses, including a store on south Main Street that was eventually bought and renamed the Blue and White Store. The North of 53 Consumers Co-Op store sits on the site once occupied by Russick’s store, while the site of his old house on Centre Street is now home to the Flin Flon Aboriginal Friendship Centre.

In his later years, Russick and his family separated from his wife and moved to The Pas, buying and operating the Rupert House Hotel.

“My grandpa lived in the hotel and we lived in the hotel as well, my dad’s family,” said Dunlop.

“There were five of us kids. It was a 24-hour business, so my dad would take the night shift that night and my grandpa would take over at six in the morning for a couple hours. I remember sitting with him in the lobby – I was about six years old – and he would give me piggy-back rides.”

While Russick passed away decades ago, for his family, his memory is far from forgotten. A lake located between Pukatawagan and Flin Flon – not far from his old hunting territory – is named Russick Lake after him. Even today, Dunlop is rediscovering artifacts from her grandfather’s time as a champion musher – including a shamrock that was given to Russick as a reward in 1924.

“I remember because some Irishman pinned a shamrock on (his) chest – March 17, 1924. My grandfather had this shamrock pinned to a piece of paper. It’s a nice keepsake that I never realized I had.”

During Russick’s time at the reigns, a poet wrote five stanzas about him and his style of racing. Dunlop still has a copy.

“For a racing team of canines; Is his stock-in-trade indeed; And racing is where ‘Shorty’ shines; Like a falling star for speed,” it reads.