When a fresh-faced Andy Arsenault joined the Flin Flon RCMP in the late 1960s, he couldn’t have known how quickly he would make an impact in policing.

In just one year, Arsenault would become one of the province’s most celebrated – and reviled – law-enforcement figures, after a historic sting that unfolded like something out of a crime novel.

“I was just a young officer who did what he was told,” Arsenault tells journalist John Einarson today.

According to Einarson, the story began in the fall of 1969 when the provincial level of the RCMP approached Arsenault, then 24, with an unprecedented assignment.

Desperate to seize drugs from the streets of Winnipeg, the Mounties needed an inside man. And they saw no better place to start than in the Manitoba capital’s music scene.

They wanted Arsenault to join a rock band. He would play Winnipeg pubs, actively seeking out drug suppliers while keeping his true identity hidden from everyone, including his bandmates.

Arsenault, who had sung in rock bands back in his native PEI, took the job. It was the first – and to date last – time the RCMP used a musical group as cover.

Einarson, who recently chronicled the story in the Winnipeg Free Press, said Arsenault had only been in Flin Flon, his first posting, for about three months at the time.

“The head of the Manitoba RCMP came up from Winnipeg to see the Flin Flon detachment and when he met Andy, they discovered they were from the same vicinity in PEI and knew many of the same people,” Einarson tells The Reminder. “The head recommended Andy for the undercover course in Winnipeg and after Andy completed the course and returned to Flin Flon, he was soon transferred to Winnipeg for the band sting. If it hadn’t been for that connection, it’s not likely Andy would have ended up in that sting operation.”

Given the eight-hour gulf between Winnipeg and Flin Flon, and Arsenault’s brief tenure in the latter community, there seemed little concern the sham singer’s ruse would unravel.

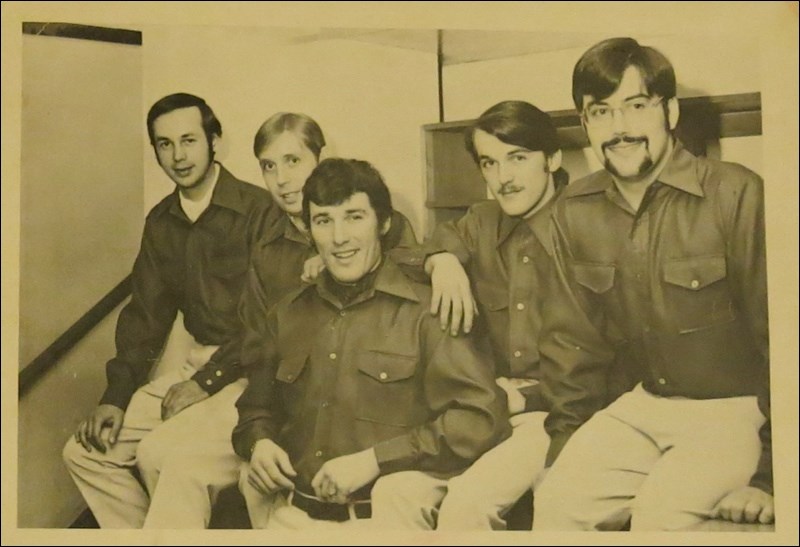

Around October 1969, Arsenault, using the alias Andy Taylor, joined a band with four other men that became known as Prodigal Son.

As Einarson recounts, over the next 10 months Arsenault made more than 200 buys of illegal drugs. When the covert operation ended in July 1970, police charged 69 people.

The case grabbed widespread headlines, and the backlash against the RCMP’s tactics was swift.

“It was a total freak show afterwards,” Arsenault, who feared for his life, tells Einarson.

“Young people really turned against me. In court, I was kicked by people. I had to get out of town.”

Not everyone despised Arsenault. As Einarson notes, a Winnipeg pizza restaurant took out a newspaper ad offering the officer a free pie if he stopped by.

Valuable?

Einarson, himself a Winnipeg musician at the time of the bust, still questions the value of the sting.

“It was certainly controversial and put the music community on alert,” he says. “I think the mission netted too many small fish and not enough of the big fish.”

In the 45 years since the famous bust, Arsenault had never before granted an interview about the case. The Reminder could not reach him for comment, but Einarson did.

Today Arsenault is past retirement age but spends his days running a security company in eastern Canada.

“I found him very friendly, forthright and proud of his 30-year RCMP career,” says Einarson. “He had nothing to hide in our interview and was extremely honest about the case. He expressed sincere remorse that he had to deceive his bandmates, who were his friends. But he had a job to do.”