Flin Flon could figure prominently into an ambitious proposal to open the floodgates to northern Canadian development in the coming decades.

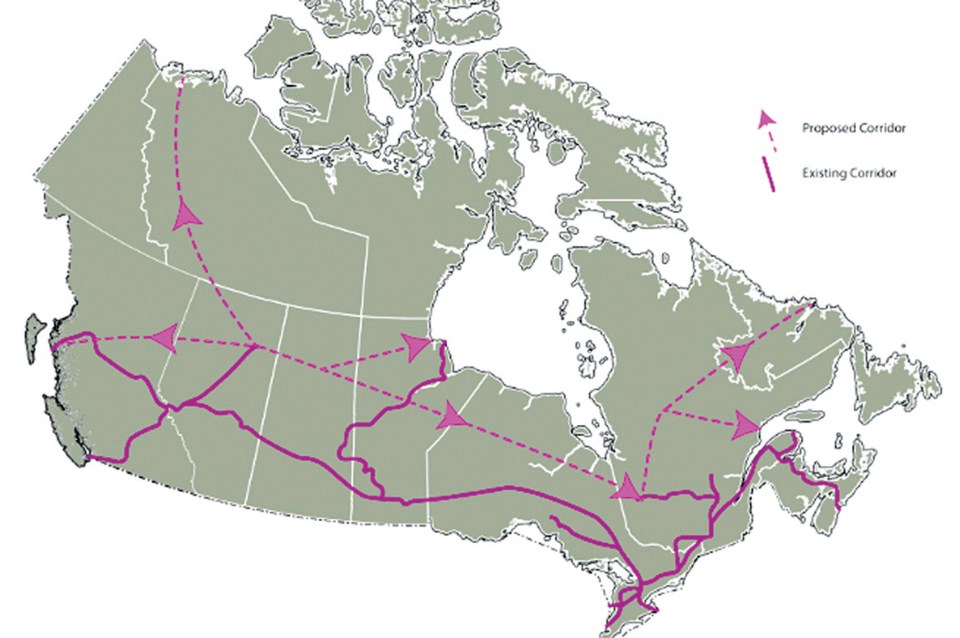

The Northern Corridor is envisioned as a coast-to-coast transportation route featuring some 7,000 km of highway, railway and other infrastructure across the northern portion of the country.

The corridor is only an idea at this stage, but a preliminary map shows the passageway would pass right by Flin Flon – potentially spurring significant growth.

“There’s certainly a potential that it could become one of the hub cities on [the route],” said Kent Fellows, a professor with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and a researcher of the proposal.

“One of the next phases of our research is to look where population centres are already, where resources are located and try to figure out, what are the main areas that we can hit? So Flin Flon is definitely on the radar from that perspective.” It’s difficult for Fellows or anyone else to speculate about what impact the corridor could have on Flin Flon and other communities along the route.

That would depend on whether the passageway succeeds in spurring the resource sector and, as a bonus, lowering a cost of living that many northern Canadians find difficult

to bear.

Fellows draws the possible parallel of the CN main rail line. He says his home city of Calgary didn’t have a post office until the line arrived and went from “essentially nothing” to its current status.

“So when we talk about cities or towns that would be on or near that [Northern Corridor], you can imagine that there would probably be some considerable induced growth for a number of different of reasons,”

he said.

For northern Canada as a whole, Fellows said the corridor could be as transformative as the CP main line and Trans-Canada Highway were for southern Canada.

Right-of-way

The Northern Corridor would begin as a pre-cleared right-of-way spanning from the coast of BC to the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, with branches extending to the coasts of the Northwest Territories and Quebec.

The right-of-way would be as wide as a kilometre, possibly wider in some parts, and preapproved for infrastructure – highways, railways and possibly pipelines, hydro lines and fibre-optic lines – by all jurisdictions involved.

“So something…where we say, ‘Okay, this is where the corridor is, so we’re pre-cleared, we’ve done all the surveying, if you want to build a railroad, you build a railroad here. If you want to build a highway, you build a highway here,’” said Fellows.

“[If] you actually put this infrastructure in place for transportation, it will be sort of a chicken and egg thing, that I think development will beget development.”

Fellows envisions the corridor materializing on the strength of government and private-sector investment.

If a highway were to be built, it would likely be fully or partially funded by government. If a railway or pipeline goes in, industry could foot the bill.

“It’s really about facilitating that infrastructure development, not driving it, so we’re moving the obstacles rather than trying to incentivize it,” Fellows said. “I think the incentive to build a lot of this stuff is already there. We just have a lot of administrative obstacles that are preventing that kind of investment.”

Proponents of the corridor assert that northern Canada is replete with untapped natural resources. Improving accessibility to the region, they believe, will generate jobs and wealth for the country.

Fellows agrees industrial opportunities are key to the proposal, but he hopes people will not overlook the potential of a lowered cost of living for northern Canadians.

New transportation infrastructure, he said, would lower shipping costs for consumer goods and building materials.

“There’s a huge potential to increase the quality of life, and as you increase the quality of life in a region, we tend to see population inflows, capital inflows and that kind of growth,” Fellows said.

Fellows also believes improved accessibility to natural resources could replace fly-in communities, whose workers spend their earnings in cities such as Edmonton or Calgary, with stable ones.

“I think over the longer term, we need to look at these as places to work and places to live so that we don’t end up with these fly-in communities where you go in, you pull everything out and then you’re gone,” he says.

Long term

Fellows is clear the Northern Corridor is a long-term plan for long-term development. He views the passageway as part of a national plan with the next 50 to 100 years in mind.

He and his fellow researchers – the corridor concept is led by the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and Montreal’s Centre for Interuniversity Research and Analysis of Organizations (CIRANO)– have about another three years of study ahead

of them.

If the project proves feasible and finds support from government, Fellows believes the right-of-way could be finished within two years of its inception, and then open to infrastructure projects on an as-needed, as-wanted basis.

Since entering the public sphere in mid-2015, the Northern Corridor idea has captured the imagination of some key figures.

Earlier this year, the Standing Senate Committee of Banking, Trade and Commerce endorsed the proposal and urged the federal government to take a leadership role in building a national corridor.

As a start, the committee urged Ottawa to provide a $5-million research grant to the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and CIRANO.

So far the government has not obliged, but some senators seem poised to keep pushing.

“Not since Sir John A. Macdonald’s National Policy in the 1870s has Canada had such an opportunity to build such a monumental infrastructure project with the potential to transform the country’s economy,” said Sen. David Tkachuk, chairman of the committee, in a press statement. “As Canada looks forward to its next 150 years, a national corridor is the kind of infrastructure it will need to tap into new foreign markets.”

The Northern Corridor is not the first proposal of its kind. In the 1960s and ’70s, lawyer Richard Rohmer devised a plan for the Mid-Canada Development Corridor, a multibillion-dollar strategy to develop new mines, industries and transportation networks across the Canadian North.

By virtue of its central and resource-rich location, Flin Flon would have been a hub city along the Mid-Canada route, projected to grow to a few hundred thousand people by 2000.

While many have dismissed the Mid-Canada proposal as pie-in-the-sky, Fellows believes the new Northern Corridor concept is wholly viable – with the proper mindset.

“I think it’s absolutely realistic if we’re realistic about the expectations that this is not something [where] we’re going to elect a government and they’re going to do it in their four-year mandate. No, that’s definitely not reasonable,” he said.

“It’s really a plan for sort of the next half-century or next century of the country in terms of setting up the transportation infrastructure.”