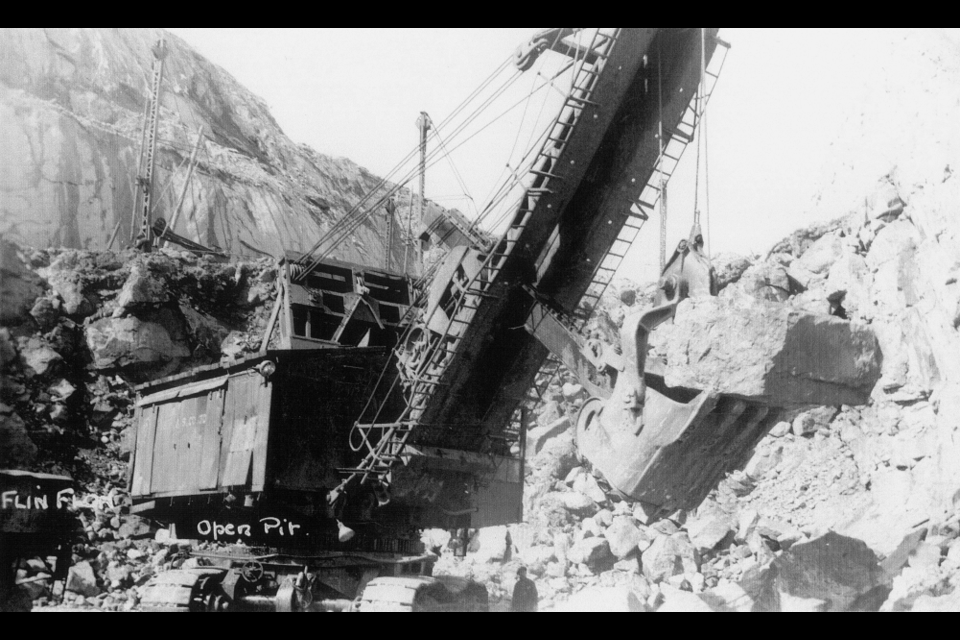

It was one of Flin Flon’s original building blocks, a tall, mean, 60-ton electric shovelling machine, used to dig out the city’s biggest project to date in its time - the original open pit.

It was the Marion 4160 electric shovel and it, perhaps more than any other piece of the mine, was responsible for mining in Flin Flon as it is today.

Electric-powered and mounted on tank-like tracks, the Marion shovel was a machine designed to do the work of dozens of labourers of minimal effort. The shovel was built by the Marion Power Shovel Company out of Marion, Ohio and was a large, tractor-like vehicle with a large arm extending up over the tracks. A pulley, cord and gear system was used to power a giant scoop up and down.

Marion shovels were used in many 20th century projects that required moving large amounts of earth, fast - the Panama Canal was built using over a hundred Marion shovels. The Klondike Gold dredges at Dawson City, Yukon were built with Marions. One of the world’s largest mines, the Magnitogorsk iron ore mine in the Soviet Union, was built using Marion shovels.

When it came time to build an open pit in Flin Flon in the late 1920s, the Marion shovel was the way to go. The first shovels arrived in town in 1929.

Different types of Marion devices, big and small, were used in Flin Flon. The biggest was the 4160, not the same kind used in Panama or the Yukon - a rumour that one of the shovels used in Flin Flon was used to build the canal is likely incorrect - but a smaller, more mobile version, almost tailor made for the pit.

“The 4160, with its four-cubic-yard bucket capacity, was as modern as anything offered by [competitors] at the time and was considered one of the largest intermediate-sized shovels available to the mining industry during the early 1930s,” reads a passage in the book Power Shovels: The World’s Mightiest Mining and Construction Excavators, written by Eric C. Orlemans.

Estimated at around sixty feet tall at the top of the arm, the shovel dug out earth at record time. Two 4160s were used to help dig out the pit. A report from the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy said the shovels were able to dig out between 1,000 and 1,500 tonnes of material in a 10-hour span.

“They were both used when they were first brought to Flin Flon to dig out the open pit,” said historian Les Oystryk. A former conservation officer turned local historian, Oystryk has helped preserve the memory of the 4160.

“Those are the two pieces of equipment that were really responsible for excavating all the blasted rock to get to the bottom of that huge open pit. I don’t know if they used 24-hour shifts or what, but to move that amount of rock, it was huge.”

Other pieces of Marion equipment, including cranes, were used elsewhere during the project. Cranes with the Marion imprint hauled freight to help build and maintain the mine off sleighs and train cars.

“You’ll see photos of them way up on surface when they just started to dig that pit - then later, there’s some where you can see the shovels way down at the bottom. Mega, mega tonnes of rock were removed with those Marions - mega tonnes,” said Oystryk.

Change of times

The first chime of doom for the 4160 was the transition for Flin Flon from being based on the open pit toward closed, underground set-ups. The shovels had been used to dig further at the pits, but would be next to useless at building anything underground. Like using a fork to eat soup, the 4160 was the wrong tool for the job.

“When the open pit ceased operating, that’s when either one or both of those shovels were taken back onto surface. They may have been used to move rock or slag on surface for a while,” said Oystryk.

Another problem came in 1955, when one of the 4160s ran over and killed an HBM&S employee, according to a Saskatchewan Department of Mineral Resources report.

Once the machines began showing signs of age, they were repurposed. One of the 4160s more or less disappeared - historians have conflicting stories as to where it may have gone. Other, larger machines began being used for open-pit mining. The 4160 was quickly becoming obsolete.

In the latter days of its use in Flin Flon, the sole remaining 4160 was driven north of the HBM&S compound to Mari Lake, where it was used to dig out and load sand to be used as a flux agent in the company’s smelter. Sand dug out by the shovel would be sent directly to the mining complex via a rail line, where the sand would be added to molten ore to extract impurities from the material, leaving two products behind - valuable concentrate and the jagged, matte black rock Flin Flonners know as slag.

Later in the ‘90s, the process for purifying ore changed. Mari Lake sand was no longer needed to the same extent, leaving the shovel without a job for the first time in over six decades. The quarry went quiet.

“The company was in the process of fulfilling their requirements to quit claim those leases and to revert that land back to the crown. They were required to remove any sort of manmade materials - timbers, steel, buildings, railroad rails, that kind of thing,” said Oystryk.

When the shovel was no longer needed in the late 1980s, one final task was required. Not far from the Mari Lake quarry, the shovel was used to dig out a sixty-foot hole, which it was then piloted into and buried.

In essence, the shovel was used to dig its own grave.

“The company received approval to just bury it, long story short,” Oystryk said.

The last reported official sojourn to the shovel site was back in the mid-1990s, only a couple years after it was buried. Dennis Strom, a Creighton-based historian, was part of the group that headed north to find the shovel. Almost nothing remained, except a few inches of the top of the crane, poking out of the sand.

“I went in there in 1994 with an industrial archeologist and a couple of local people and we went and located it,” said Strom.

“That was the last time I was back in there. We found the top of the shovel, one of the arms itself, was exposed.”

Rebirth?

While the shovel has almost certainly dug its last load, local historians have bandied about the idea of digging it up and showing it off as a key part of Flin Flon’s mining history.

“Even back then, almost 30 years ago, there was some thought given to bringing it out of that place, as remote and as difficult as it may be, and putting it on display somewhere. It’s part of historical mining activity out here, but it never materialized,” said Oystryk. A Creighton resident and archeology buff, Oystryk has been one of a number of people pushing for the shovel to be preserved.

“There’s been some interest in what to do with it or what should be done with it. Recently, there’s been a couple of people who’ve expressed an interest to see whether there isn’t some way to bring that piece of equipment out, or at least to expose it so it can be appreciated.”

The big trick is in how the shovel can be moved. The area where it rests, not far from the lake’s southern tip, is overgrown with bush. The shovel still sits there, somewhere, underneath the bush and tonnes of earth in unknown condition. Excavating the shovel would be expensive and possibly treacherous. If excavated, moving it may prove difficult.

One solution mentioned is to cut the machine up at the site and transport it in pieces. Strom isn’t a fan of that idea.

“There’s been interest expressed in doing something with it, but the solution at hand, in my estimation would be more destructive than beneficial. There was talk of cutting it into bits and pieces.”

“The problem with that is you lose a lot in there. It’s a fairly destructive means of trying to preserve a piece of equipment.”

“There was some company down in the U.S. that had one and just in the last couple years, they scrapped the thing, cut it up and sold it as scrap metal. What else do you do with an old piece of equipment like that, if you don’t know of any other reason?” added Oystryk.

The shovel is known to be on the Saskatchewan side of the provincial border. Strom wrote a letter to Creighton town council and the provincial heritage branch earlier this year asking for support in preserving the shovel area as an archeological site.

“To get it out of there would require lots of money and lots of effort to do it properly,” he said.

A group based out of Ohio, the home state of the company that built the shovel, has apparently shown some interest in the project.

“I’ve spoken with a couple people from that branch of government and they certainly see it as being a significant archeological artifact,” Oystryk said, adding an expert on the machines from Alberta had also shown interest.

“He’s written a number of books about this type of equipment and he claims it would be the only example in its original form of the Marion 4160 anywhere in the world. We kind of think it would be pretty special.”

The best case scenario is to move the shovel out and put it on display to provide a better record of how Flin Flon was built, Oystryk said.

“I think it’s worth making it available somewhere, somehow, to show people the size of this piece of equipment and how important it was to the life of the Flin Flon mine,” he said.

“In that day and age, there was probably no other piece of equipment that could do what the Marion 4160 did.”