Cabbage would seem to check a lot of boxes for what's prized these days in Western food circles. It's nutritious and inexpensive. Seasonal. Colorful. Climate-hardy. Fermentable.

So why does it still struggle for respect?

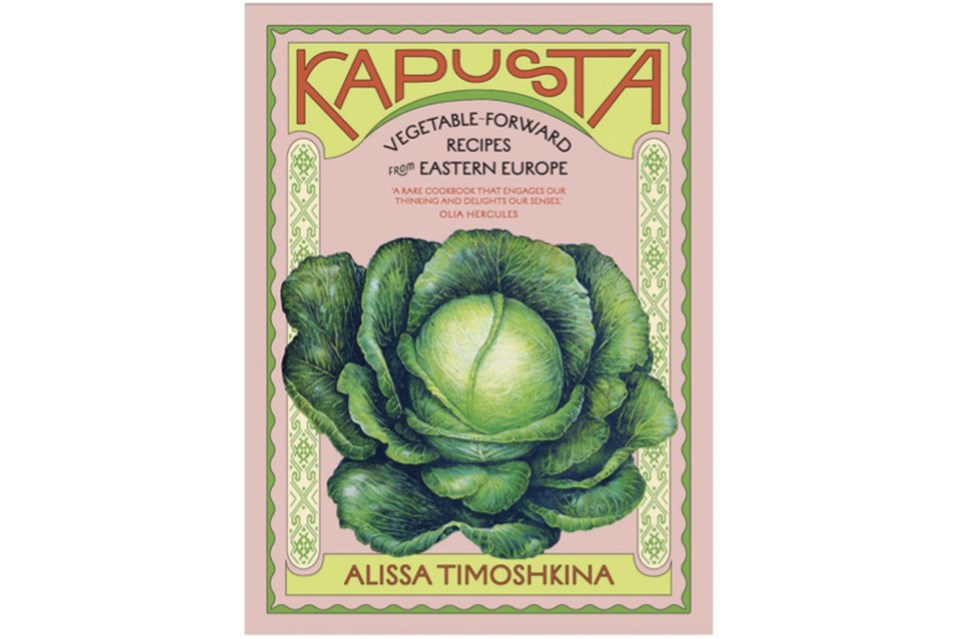

“It's about how you cook it. People tend to overcook it, not letting it express all its potential,” says Alissa Timoshkina, whose new cookbook, “Kapusta: Vegetable-Forward Recipes from Eastern Europe,” celebrates cabbage as one of the backbones of the region's cooking. ("Kapusta" means cabbage in many Slavic languages.)

The other mainstays, she says, are beetroot, potatoes, carrots and mushrooms; each gets a chapter, along with dumplings and “ pickles and ferments."

Although cabbage has sometimes conjured up images of poverty and bleakness (Timoshkina mentions “1984” and “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” as two famous examples), she sees it winning wider recognition in a kind of East-West culinary meeting of the minds.

“There's a natural crossover,” she says, given today's greater focus on vegetables and simple, healthy ingredients. In Eastern Europe, “there's almost a sacred reverence” for these foods, “whereas in the West, it's coming from a different place: awareness of your responsibility for climate change, sustainability. People are starting to think about how we eat differently.”

Take the current interest in fermentation, for example.

“I love the fact that I’m not just catering to a trend, but it’s actually talking about a culture and a tradition centuries and centuries back,” says Timoshkina.

She notes that cabbage also has a magical quality in folklore — the legends that children grew in cabbage patches, or that cabbages could increase fertility.

What they're eating in various countries and ethnic groups

Timoshkina, who was born in Siberia in a Ukrainian-Jewish family, moved to England as a teenager and became a food writer, cook and historian. Her previous cookbook, “Salt and Time,” featured recipes from Siberia and other parts of the former Soviet Union.

There are various ways to define Eastern Europe, she notes. She follows the U.N.'s definition, which includes 10 countries, and she includes even more ethnic groups. She generally avoids referring to Russia, however, because of its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. For its part, Ukrainian food has a large role in the book.

The recipes in “Kapusta” range from savory pies ("Patatnik," for example, a Bulgarian potato pie) to cold-weather stews (such as Ashkenazi “Tzimmes” with carrots, beef and prunes) to summery dishes ("Chlodnik," a cold borscht with kefir). They go from basic ("Classic Sauerkraut") to more adventurous (“Taratuta," a Ukrainian beetroot, gherkin and horseradish salad).

Also typical of the region's cooking, she says, are paprika, coriander, caraway, fennel, dill and pepper. And lots of sour cream.

Dumplings and stuffed cabbage

Timoshkina considers dumplings the ultimate comfort food, though she acknowledges they take some time to prepare.

“It's probably something you do on a weekend and then you'd make a big batch,” she says. “You can store it in the freezer, and you always have yourself a lovely, comforting meal.” Dumpling recipes here include “Polish Pierogi with Sauerkraut and Mushrooms" and “Udmurt Dumplings with Beetroot and Raspberry."

And then there are cabbage rolls, or stuffed cabbage. They're called gołąbki in Poland, halupki in Czechia and Slovakia, szárma in Hungary and sarmale in Moldova, to name just some, she writes.

Here too, make a big batch and freeze them.

“It's an iconic dish that people from every region of Eastern Europe have their own version of,” says Timoshkina. “Everyone claims them as their own.”

Julia Rubin, The Associated Press