When Ron Burwash talks about music, he talks about Métis culture. When he speaks about Métis culture, he talks about music.

The two connect, much like the white infinity symbol on the Métis flag – a flag Burwash flies proudly.

Burwash was born in Flin Flon, but spent a lot of time in his grandfather’s hometown of Boggy Creek, a place that still holds significance for him. It is where Burwash does a large amount of his hunting and where his grandfather lived before he was sent to school in Winnipeg.

“That’s where he learned how to speak English – never spoke a word of English before that. Nobody did around the house,” said Burwash.

“When he came home, not hearing French for a whole year – it was kind of funny – his brothers and sisters were laughing at him because he put the horse in front of the cart. It didn’t last very long, but he’d lost it a bit,” said Burwash with a hearty chuckle.

Between his family’s old home in Boggy Creek — near San Clara in southern Manitoba – and his permanent home in Flin Flon, Burwash couldn’t escape music – not that he’d ever want to.

Growing up Métis meant Burwash heard one instrument more than any other. The sound of a fiddle still brings Burwash back to the old days.

“Growing up, I used to listen to the fiddle. That’s a big part of Métis culture, the fiddle. It’s important,” he said.

Some things continue to bring Burwash back to his childhood and times in Boggy Creek, where the adults spoke Michif and the kids got up to mischief.

“It could be a mixture of Saulteaux, French and English or it could be Cree, French and English. They’d talk softly,” he said.

“I’d be listening to my aunts and uncles talk, maybe somebody had come by, and they’d sit and they’d have tea and talk. They’d talk about different things. I’m sitting there, not understanding Cree, but when they used French, I would sort of know what they were talking about,” said Burwash.

Music

Thinking back to his younger years, Burwash can remember a few key places where dancing, music and fun could usually be found – especially the Jubilee Hall, located not far from the HBM&S compound.

“We’d have dances in there. When my sisters and them were younger – I was really young, like five, six years old and they weren’t married yet – they used to go to dances there and at Phantom Lake.”

“The music scene around here, I think today is maybe the best it’s ever been, but when I was young there was a lot of really good bands around and fiddle players.”

Burwash was drawn to playing music from a young age, having been surrounded with music through his family’s traditions and his neighbourhood pals.

“On the street that I grew up on, there was three or four people who used to play music. They were friends of mine, so I kind of went with them,” he said.

“I always liked music. My mom always used to play it. We had a record player growing up, so I loved it since I was young. I think it comes a bit from growing up and seeing the Métis cultural side – lots of music, lots of singing. Friends of mine played music and that was an influence on me. I always liked it so much.”

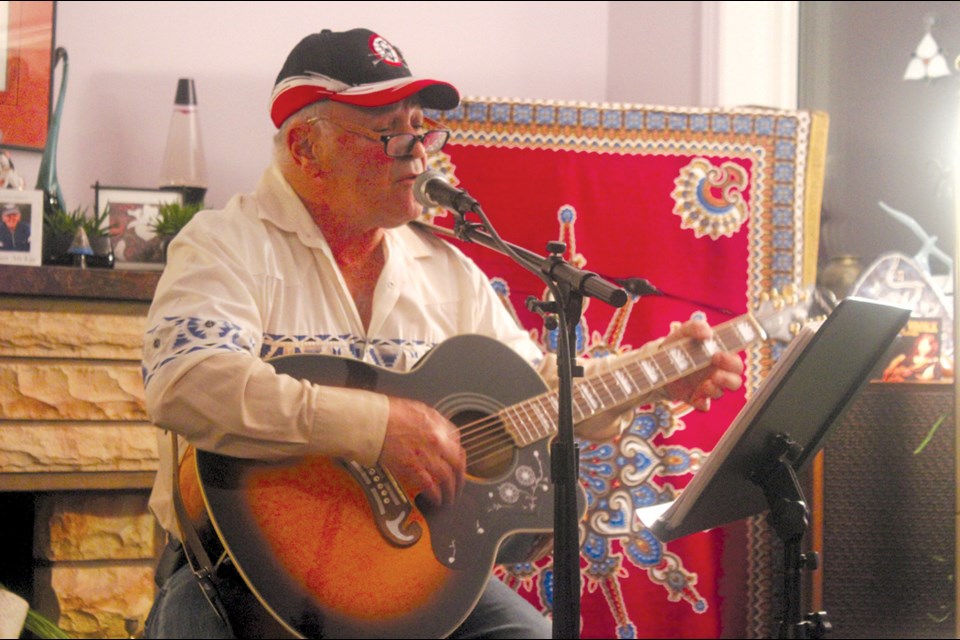

He picked up a guitar as a young man – he’s rarely put it down since.

Bomber days

Today, Burwash is most well known for his guitar work and his performances, both around Flin Flon and across Western Canada.

Fifty years ago, Burwash was maybe more recognizable for how he handled another wooden object – a hockey stick.

Along with childhood pals Bobby Clarke and Tom Gilmore, Burwash made a name for himself as a feisty forward with the Flin Flon Bombers. Burwash suited up for four seasons in maroon and white, winning a WCHL regular season title in 1969 and making the Memorial Cup playoffs with the Bombers in 1967.

Burwash and his two buddies first made the team as midgets in 1966. While those days may feel like a lifetime ago, Burwash still remembers them clearly.

“We were allowed to play three or four games a year. I got my first goal against the Moose Jaw Canucks. We won that game 5-2 or 5-1, and I scored a goal, Bobby scored a goal and Tommy scored a goal, that whole line had a good Saturday night.”

“There was about 1,400 fans, you’d always have about that many since there was no TV back then.”

The thing that stuck out the most about that game wasn’t the goal or his friends’ success – it was a nasty accident late in the game.

“One of our defensemen, a local guy who made the NHL, he hooked skates with another guy and as he went to skate away, he yanked the Moose Jaw kid’s hip bone right out of his socket. You could hear that kid screaming over the fans.”

In the end, it was the brutality of ’70s era hockey that kept Burwash out of the pros. After he became too old to play for the Bombers, Burwash went to training camp with the Philadelphia Flyers, sharing a dressing room with Clarke and a couple other Flin Flonners at the height of the Broad Street Bullies.

“I never went to Philadelphia’s camp until I was 24. By that time, I realized, ‘they’re not looking

at me,’” he said.

Instead of bouncing around the minor leagues, Burwash returned home. Some of the lessons he learned in his playing days still stay in his mind decades later.

“I think what I learned from then to now, what sticks out in my mind is that it was a great time. I met a lot of people and you think about them, hope they’re doing well. We’ve lost a few along the way. Respect, I guess. Having respect for everybody is a key thing,” he said.

Embracing tradition

After leaving hockey behind, Burwash kept performing and kept spreading his knowledge of Métis traditons and customs.

As far as Métis bloodlines go, Burwash has an impressive family tree.

“Cuthbert Grant, he’s an uncle to me – with many ‘greats’ in front of it. He’s the first guy to fly the Métis flag, at the Battle of Seven Oaks. You have Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière, he’s my grandfather with many greats. So is Louis Riel, his grandson,” he said.

“I can honestly say, if there’s royalty in the Métis Nation, I belong to it,” he added with a deep laugh.

While Riel remains a controversial figure for some more than 130 years after his death, Burwash views him as a misunderstood hero.

“As Manitoba Métis, we’re proud of him, and I think other Métis people are too. He wasn’t afraid to stand up to the government. Other people do too, but they don’t go to war over it!”

Once Burwash spoke about Métis culture, talking about music wasn’t that far behind.

Burwash told a story about a recent return to Boggy Creek. It didn’t take long before someone broke out a fiddle.

“I don’t go down there without going to the Métis Hall in San Clara. We have breakfast there and I visit all my old friends that I knew as kids. The fiddle comes out at nine o’clock in the morning and we’re all playing songs,” he said.

“Every morning, that happens. There’s a fiddle hanging on the wall, they keep those strings in relatively good shape and they have a little go-around for a half an hour.”